It was a beautiful, sunny September morning.

The booths of Salone de Gusto, the biannual Slow Food festival, filled up Turin’s Piazza Castello.

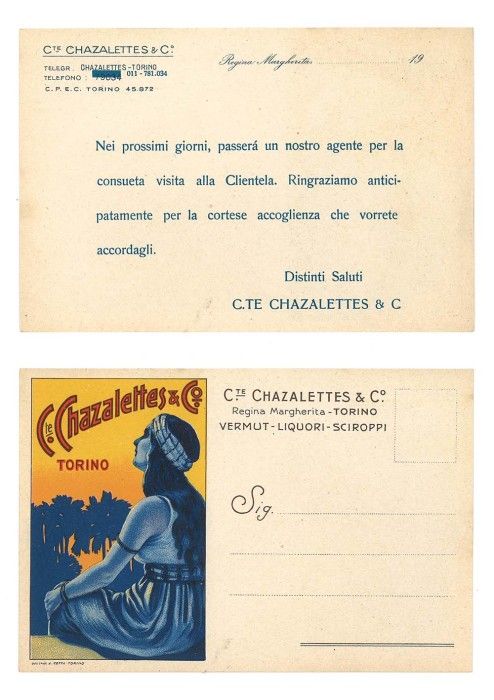

A drunk bartender had knocked down a heavy barstool on my left foot the night before. I was limping, in pain, but things were looking up: I was there to witness the reintroduction of Chazalettes, a vermouth brand that had disappeared decades ago. The official presentation was organized in the cafeteria of the Palazzo Madama, in the baroque wing designed by architect Juvarra in the early 18th century.

The setting appeared grand for what was, after all, a modest affair of about 20 guests. But it made sense: Chazalettes was one of the big ten in the early 20th century and had royal pedigree – it was allowed to bear the Savoy coat of arms and dedicated one of their bottling to Queen Margarita. Vermouth was developed in Turin as a drink fit for princes and early versions were primarily consumed by the wealthy. Over two centuries later, echoes of that aristocratic past can still be felt.

The presentation was part of a wider initiative put together by Cocchi, the producer who partnered with Giovanni Chazalettes to bring back his family’s brand. Cocchi launched for the length of Salone del Gusto a Vermouth Pass, with VIP access to various exclusive events, including tastings, chocolate pairing, vermouth ice cream, rooftop cocktails and dinner at one the city’s most prestigious restaurant. It was all very exquisite, as you’d expect from one of the pioneering producers of the vermouth resurgence.

A week earlier, I had visited the small city of Reus, in Spain, for another vermouth event, Expovermut. The contrast was obvious, with a dozen wooden shacks set up on a charmless square just outside the historical centre of this old Catalonian trading centre. The brainchild of Joan Tapias, owner of the restaurant-cum-museum Museu del Vermut and probably one of the world’s most knowledgeable vermouth drinkers, Expovermut gathered about twenty brands, many of them from the area. None of the exclusivity of Cocchi’s Vermouth Pass: the event was aimed at local, everyday customers who just had to buy a few tickets to enjoy vermouth samples and small food items while listening to music.

If Turin celebrated a product with pomp, Reus seemed to celebrate a social ritual. Reus, this is little known outside of Spain, is the cradle of Spanish vermouth. As such, and on a smaller scale than Turin, it has assumed an important place in the historical development of vermouth. And even though brands such as Carpano and Cinzano have fled Turin and Spanish production is not limited to Reus, they remain at the epicentre of vermouth culture in their respective countries – and indeed the world. So the different ways they seem to be looking at vermouth today will have an impact, if local producers play their cards right, on the directions the vermouth renaissance takes next.

Turin is of course where everything started almost 250 years ago. A rich city with a long liqueur making tradition, it’s ideally located, with the herbs of the Alps to the north and the vineyards to the south. A logical start point for an alpine wormwood-based aromatized wine. Especially when you factor in the proximity of the harbour of Genoa, where ships unloaded tons of spices from the orient and loaded the new product that was to be sent towards the Americas and their growing Italian communities.

In a way, Reus tells the same story. For sure, it’s not as close to the mountains (200 km from Andorra) and while the harbour of Salou is only a 15 minutes ride, it wasn’t fully functional when Reus vermouth became a thing, but they still have many things in common. Throughout the 18th century, Reus acquired a reputation for producing some of the best eaux-de-vie in Europe. They were providing the Dutch market and even the French when Cognac producers couldn’t keep up with demand. Reus was (and still is) surrounded by vineyards. Much like the whites of Piedmont that were used to make Turin vermouth, Catalonian wines of the time found little favour on the market and, as such, vermouth was an opportunity for local producers to diversify and sell the surplus.

It wasn’t however until the 1880’s – half a century after Turin brands had launched their international expansion – that Reus’ vermouth industry really got started. It wasn’t driven by craft spirit geniuses, but rather by apt commercial operators who were able to see a unique opportunity when it came knocking. In 1881, Spain’s conservative government had hiked taxes on foreign manufactured products – including wine. All of a sudden, French and Italian vermouths that had slowly but surely gained some modicum of popularity in Barcelona and other big cities became considerably more expensive – unsurprisingly, local alternatives sought to take their place.

Simple & Yummy with Vermouth!

Pearl Fisher No 3.40 ml Vermouth Red

10 ml Falernum

Top up with Tonic Water

Method: Build in glass over ice cubes or ice collumn

Glass: Highball

Garnish: Lemon Peel

Starting off as imitators, Reus producers still benefited from some help from the ones they sought to emulate. In order to circumvent the law, Martini set up its first production plant outside of Italy in 1882, allowing them to pay the reduced rate. For the move to make sense, they had to start pushing their product harder, which helped the category as a whole. The head of their Spanish operation opened two luxurious establishments in the centre of Barcelona (famous artists such as Gaudi were involved in their designed) who played in huge part in transforming the drink into the aperitif of choice for the enlightened, liberal bourgeoisie.

Over the following decades, the industry in both countries followed similar patterns: the market grew exponentially and from an elitist drink called, not for nothing, ‘vino de lusso’ (luxury wine) in Italy, it gradually became something the popular classes would drink on their day out – if Martini and Cinzano played the Dolce Vita card over the last decades, one shouldn’t forget that vermouth was an aspirational drink for many of the socially upward low-middle class workers who benefited from the 50’s and 60’s Italian miracle. In Spain, vermouth was initially linked to theatre – a matinée was called a ‘sesion vermouth’ – but, in the 50’s, when the economy at last grew after the devastation of the Civil War, national brands got to sponsor the football liga. It even went crashing down at the same time in both countries: the market shrunk down rapidly in the 70’s, under the pressure of changing trends, globalized tourism and the lack of modernization of the industry.

And yet, as my experiences of early September indicate, both cities relation to vermouth couldn’t be more different. Two crucial aspects better explain this: exports and the way the stuff was drunk. Italian vermouths were exported from the 1830’s and reached American shores en masse in the 1880’s. Initially drunk exclusively by the Italian communities of Brazil, Argentina or the USA, it became an essential part of the incipient cocktail culture. And while it remained something that was drunk on its own for decades in Italy itself, local bartenders came up with their own mixed drinks, such as the Americano or the Negroni. Slowly but surely, they took over, to the point that by the 1980’s, vermouth was essentially drunk mixed.

In Spain, though, this process never took place. First, no Spanish brand saw significant export numbers. Cinzano and Martini were leaders in Spain too, and the preferred choice of cocktail bartenders. Spanish vermouth brands mostly sold locally – in big volumes, but locally. Cocktail culture didn’t really develop either, although American-style mixed drink made with vermouths such as the Bronx, the Martini or the locally created Media Combinacion (two parts sweet vermouth, one part gin, barspoon orange liqueur, dashes of Angostura) were extremely popular in Madrid and Barcelona in the 1920’s and early 1930’s, but the Civil War between 1936-1939 prevented this modern trend to take root – another victim, albeit more anecdotic, of this gruesome conflict. And so to this day, Spaniards drink their vermouth (relatively) unmixed – maybe with a bit of soda, and in some regions, with a few drops and dashes of spirits and bitters. The consequences are obvious. Italian vermouth has become a tool for cocktails. When the cocktail renaissance started taking shape and bartenders went on the look for authentic, quality products that could work in their drinks, Italian producers naturally responded by introducing more intense recipes, bringing back (supposedly) the flavours of late 1800’s vermouth, the very ones used by American bartenders to create the Manhattan, the Martinez or the Brooklyn. Unlike gin with Bombay Sapphire – an attempt to vodka-ify the category – Carpano Antica Formula, the first vermouth to play the premium card, was a reaction against the perceived loss of flavour of mainstream products. Both the cocktail renaissance and this process went hand in hand. Once it was quite clear the cocktail thing was here to stay and that great, new or not so new Italian vermouths were available, Italian producers turned their attention to the next step of development: fancy restaurants. The reasoning was that one can only fight against the Martinis of this world up to a certain point. And once you reach that point, gastronomy can provide growth.

Cocchi’s Vermouth Pass perfectly reflected this strategy. Interestingly, though, when I went for dinner with the brand’s co-owner and marketing director Roberto Bava, we realized that even the bar at the hotel where Cocchi was holding dinners where food was paired with their products, their vermouths were not taking centre stage. Cocchi Storico Vermut di Torino is now a widely known product and the gold standard for premium, authentic vermouth, but Bava remembers how hard it was to convince Turin bartenders to use the stuff in the first years. It’s an uphill struggle to make this city a vermouth capital again, admits Bava, but this is quite clearly his ambition.

In Spain, meanwhile, the recent vermouth trend has nothing to do with cocktails. In fact, Spaniards have vermouth at midday, when cocktail bars are closed. Today’s drinkers are just doing what their parents or grandparents were doing. Since the first Spanish vermouths – imitations of the Italian originals – came on the market, tastes have changed and people rejected bitterness. Spanish vermouths, being drunk straight and barely ever mixed, have gradually changed: softer, sweeter (in taste, not quantity of sugar, much inferior to their Italian counterparts), less intense. They’re vermouths people are glad to drink – and more than one glass. So new brands are not interested in going back to traditional, stronger formulas. They ‘just’ try to provide what people want to drink.

In a way, the Reus way is the ‘populist’ option and efforts to reposition Turin at the centre of the vermouth map are more ‘elitist’ (a less polemical way to put it would be to say that producers such as Cocchi wanted first to put out a product of unimpeachable quality and only then sell it to the world, which is a harder job). On the worldwide stage, the cocktail scene has largely driven the vermouth renaissance. And more and more brands come knocking at the door of restaurants. So did the Turin model win? Yes… so far! It’s of course not reasonable to expect Reus brands to rival with Italian vermouth, but our best hope for vermouth as something that is widely drunk might be coming from Spain, where it’s all about seducing the basic consumer. If we want to compare it with gin, Italian vermouth would be the traditional, qualitative, juniper forward expression that Martini lovers would want in their Martini, while Spanish vermouth has the potential to be the Hendrick’s of vermouth. As a vermouth lover, Turin, Chazalette and Cocchi Vermouth Pass is where my heart is. Those are people who strive to put the best product out there. As a vermouth expert, though, I dream of Reus being the trendsetting city it never was.

François Monti is a vermouth, spirit and cocktail writer & educator, born in Belgium but based in Madrid. He’s the author of 3 books, some of them award nominated. Hewas named in Drinks International’s Bar World 100, as one of the World’s 100 most influential person in the bar industry in 2019 and he’s one of the Writing & Media co-chairs for the Tales of the Cocktail Spirited Awards, New Orleans. For more info about F. Monti and bookings please visit:www.francoismonti.com/in-english

Read this, plus more articles like this at Fine Drinking magazine a printed only press, published by Baba Au Rum.